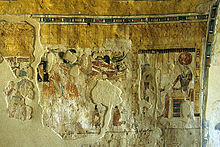

View of the archaeological site in the north of the village | ||

| Drāʿ Abū en-Nagā · ذراع أبو النجا Deir el-Bachīt · دير البخيت | ||

| no tourist info on Wikidata: | ||

| ||

Dra Abu en-Naga (also Dra / Dira Abu el-Naga / el-Nega, Dra Abu'l-Naga / Nega, Arabic:ذراع أبو النجا, Dhirāʿ Abū an-Naǧā) is a village and an archaeological site on the Nile west side at a short distance from the fruiting land and south of the village eṭ-Ṭārif or north of ed-Deir el-Baḥrī. Here are several graves of officials of the New Kingdom and the inaccessible tombs of kings and queens of the 17th and early 18th dynasties.

background

The Village Drāʿ Abū en-Nagā is one of the easternmost villages on the Theban west bank. It is located east of ed-Deir el-Baḥrī. Just eṭ-Ṭārif is more easterly. In the vicinity of the village there is one of the largest grave areas on the west bank, which has also been spared modern developments.

Decorated with an order of magnitude of 85 of the well-known 400 Official and private graves the cemetery is not only of great importance in terms of quantity. The tombs of kings, queens and private individuals from the 17th and early 18th dynasties are also located here. However, this importance could not save the area from the fact that it was hardly noticed by both scientists and tourists. Only a few individual graves have been published to date, and a spatially and temporally coherent investigation is still lacking.

To this day, huge piles of rubble still cover evidence from 2000 years of history. The royal tombs of the 17th dynasty (from 1650 BC) are among the oldest evidence, and those of the great early Christian ones are among the most recent Deir el-Bachīt monastery complex, of the ancient Paulos monastery (engl. Deir el-Bakhit, Arabic:دير البخيت, Dair al-Bachit).

Since 1991 the area has been investigated by the German Archaeological Institute under the direction of Daniel Polz, since 1994 in collaboration with the University of California.[1] One of the most important discoveries was the huge rock grave K93.11, which is probably the grave Amenhotep I. and was reused during the 20th dynasty by Ramses Night, a high priest of Amun.[2] 2001 the remains of the adobe pyramid and the tomb of the king Nub-Cheper-Re Intef localized from the 17th dynasty.[3] Since 2004, parallel excavations have been carried out at the Deir el-Bachīt monastery under the direction of Günter Burkard and Ina Eichner from the Egyptological Institute of the University of Munich. On March 22, 2014, several gold coins from the 6th century were found in the area of the monastery.[4]

In 1999 for the first time two graves, that of Shuroy, TT 13, and Roy, TT 255, made available to visitors. Amenemopet's grave, TT 148, followed in 2010.

getting there

Getting there is quite easy. From the ticket office - the ticket must also be bought here! - in Sheikh ʿAbd el-Qurna you drive or walk along the asphalt road to the north Valley of the Kings. Shortly before the junction to the valley, a short slope leads to the 1 25 ° 44 ′ 10 ″ N.32 ° 37 '29 "E begins to go to the eastern tombs.

Tourist Attractions

The graves of this group are located a short distance away. Left (south) is the grave of Shuroy, TT 13 - TT is short for Theban Tomb, Theban tomb -, and on the right that of Roy, TT 255. Above is the grave of Amenemōpet, which was only made accessible again in 2010, TT 148. To the left of the slope you can take a quick look at the excavation site of the German Archaeological Institute. The ticket, which can be purchased at the ticket office in Qurna, costs LE 40, for students LE 20 (as of 11/2019).

Photography is prohibited in the graves.

Shuroy's tomb, TT 13

The grave that has not yet been published 1 TT 13(25 ° 44 ′ 14 ″ N.32 ° 37 ′ 27 ″ E) belongs to the official Schuroy (Shuroy), chief of the plate carriers of Amun, and his wife Wernūfer, who lived in Ramessidic times. It consists of a narrow longitudinal hall, which is adjoined by a wide transverse hall. The representations of the two side walls of the first hall, which are no longer completely preserved, are arranged in two registers (picture strips), but unfortunately not completely executed, as the preliminary drawings at the entrance and in the lower register show.

On the reveals of the entrance the remains of the grave lord and his wife can still be seen in adoration. The outer lintel shows the deceased and his wife in front of sacrificial structures and gods in a symmetrical double scene.

The upper register of the left wall of the lobby shows a preliminary drawing of a gatekeeper with knives and twice the grave lord and his wife worshiping deities. The rear deities are Maat, goddess of justice, and the sun god Re-Harachte with his solar disk, who sit in a kiosk. Underneath you can see the remains of a scene in which the couple probably worship gods and the king and queen. Unfortunately the name cartridges are empty. On both sides there are sacrificial structures between the spouses and the gods. On the right wall, in the top register, you can see the grave lord or his wife worshiping various deities in kiosks. At the left end is the god Osiris in a kiosk. The deities also include crouching demons. In the lower register, the couple worships the deities Maat and Re-Harachte. At the back of the hall there is a Djed pillar on both sides of the door, a symbol of duration, on the left on the symbol of the west, symbol of the realm of the dead, and on the right on that of the east, the realm of the living. The ceiling is decorated with colored crosses and wavy lines on a yellow background, but it has no inscription.

The door to rear hall shows the grave lord and his wife in preliminary drawings on the reveals. The hall has a niche on its back wall that was intended for the statue of the deceased. The left entrance wall shows a wealth of details arranged in four registers. Above you can see gift bearers with vegetables, including the deceased and his relatives in the garden. The lower two registers are dedicated to the funeral procession, which again includes gift bearers and dancing children. To the left of the niche, in two registers, you can see a priest and mourning women in front of the mummy at the mouth opening ceremony and the kneeling grave master in front of the Hathor cow in the mountains, this is the goddess of the west and mistress of the realm of the dead. On the right you can see the scribe god Thoth, probably with the deceased, in front of Osiris, Isis and Nephthys, and underneath a man offering incense and water in front of sacrificial structures. On the northern wall of the entrance, victims are portrayed, clapping in the presence of the couple at the banquet and the seated couple with flowers.

Roy's grave, TT 255

The grave 2 TT 255(25 ° 44 ′ 15 ″ N.32 ° 37 '29 "E) belongs to Roy, the scribe and domain head of the chapel of the haremhab in the temple of Amun, who was truly loved by his king, and his wife Tawi-wai, greatest of the harem women of courage and great vowed of Hathor. The grave was probably also intended for his brother Ahmose-Nefertiri Djehuti, royal scribe and high priest of the mistress of the two countries, and (probably) his wife Buj, singer of Amun and greatest of the harem women of courage. Another couple is named in one scene, who were probably closely related to the deceased's family: Amenemopet, royal scribe and head of the barns of the lord of both countries, and his sister and wife Mutj, landlady and singer of Amun. As the Roy's title shows, they lived at the time of King Haremhab.

The grave has been at least since Jean-François Champollion (1790-1832) known.[5] The grave was not thoroughly examined and published by Marcelle Baud and Étienne Drioton until the beginning of the 20th century.

The grave consists only of a roughly rectangular, but irregularly carved chamber in the rock. The very well-preserved paintings on a light blue background, which are probably among the most beautiful of the civil servants' graves, were applied to the gypsum plaster. In the right corner behind the entrance is the funeral shaft.

At the left entrance wall (1) there are representations in four registers: at the top a man brings a calf and two baskets to the deceased and his wife, in the next two registers you see men plowing, and in the lowest register the flax harvest is discussed. On both side walls At the very top you can see a frieze with the god of death Anubis as a jackal, hathor heads and inscriptions that name the grave lord and his wife. At the left wall (2) in the register below in five scenes from the left are the aforementioned Amenemopet and his wife, as they worship Nefertum and Maat, twice Roy and his wife, as they worship Re-Harachte and Hathor or Atum and the unity of the gods, like Roy and his wife from Horus to the scales on which the heart of the deceased is weighed and found good, and as Roy and his wife from Harsiese are led to Osiris, Isis, and Nephthys. In the register below, the funeral procession is shown, to which the coffin-sleigh train, priests and mourning women belong. The goal is the mummy of the deceased at the right end, which is held by the god of the dead Anubis in front of the grave stele of the deceased and his pyramid tomb in the mountains.

On the right wall (4) only one register has been created in the upper half. It shows a priest with two mourners as they consecrate offerings with incense and water in front of the tomb lord, his wife and two other women. In the next scene a priest incenses and offers onions to the grave lord and his wife. The content of the last scene is similar to the first, but it is largely lost today.

At the Back wall (5) there is a niche in which a stele that is no longer fully preserved is kept. In the upper part of the stele you can see the barque of the Re with the couple of the deceased, below is a hymn to the sun god Re. The representations on the back wall have only survived in fragments. On both sides of the niche there were depictions of the adoring grave lord in two registers. Above it was a double scene: on the left one originally saw King Haremhab and his wife Mutnedjemet in front of Osiris and on the right a king (Amenophis I) and Ahmose-Nefertiri in front of Anubis.

On the ceiling there are colored crosses on a white and yellow background. In the middle there is an inscription with sacrificial formulas for the deceased.

A statue of the kneeling Roy holding a stele in front of him on which a hymn to Re is written probably also comes from this grave. It went on sale in 1909 and was donated to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, in 1917.[6]

Tomb of Amenemōpet, TT 148

The grave 3 TT 148(25 ° 44 ′ 16 ″ N.32 ° 37 ′ 27 ″ E) belongs to Amenemōpet (Amenemope, Amenemipet), who in the reign of Ramses III. acted as the third prophet of Amun and in the 27th year of Ramses ’III reign. rose to high priest of the goddess Mut in Ischeru. He retained the office under Ramses V. In his grave are his father Tjanefer, who bore the same title, his mother Nefertari, director of the Amun music group, his paternal grandparents, his in-laws, his wives Tamerit, director of the Amun music group, and Tamit, singer of Amun, his son Usermarenacht , first prophet of courage in Karnak, as well as his daughter Mutemwia, leader of the Amun music group, and other family members. His father Tjanefer is known for his grave TT 158.

The grave has been known since the first half of the 19th century. The first European was the Irish nobleman in 1817 Somerset Lowry-Corry, 2nd Earl Belmore (1774–1841), as can be seen from the travelogues of his doctor Robert Richardson (1779–1847).[7] He was followed by, among others. 1825 British Egyptologist James Burton (1788–1862), 1828/1829 the Italian Egyptologist Ippolito Rosellini (1800–1843), 1844 the German Lepsius expedition and others, but without a detailed publication being presented. The most recent studies were carried out by the German Egyptologist in the early 1990s Friederike Kampp (born 1960)[8] and between 1990 and 2008 by the New Zealand-Australian Egyptologist Boyo G. Ockinga.

In front of the tomb of Amenemōpet there is a courtwhich was once closed in the east by a pylon. There is a grave shaft in the courtyard and the remains of two column bases immediately in front of the grave entrance. The grave is T-shaped. It begins with a broad, shallow hall, which is followed by the longitudinal hall and the burial chapel. Immediately in front of the chapel there is a grave passage on both sides. In the left passage there are several burial chambers as well as the burial chamber of the grave lord.

The reveals of the grave entrance (1) were once labeled, the left still contains text remains. The most beautiful representations already follow in the transverse hall. The left entrance wall (2) contains representations in two registers or image strips. You can see one in the upper register sem-Priest with his panther skin in front of a deity and next to him the grave lord, as he is led to Osiris by the scribe god Thoth. Thoth and Osiris are lost. In the lower register we encounter the grave owner twice as sem-Priest how he sacrificed to his grandparents and parents. At the left narrow wall (3) the grave lord and his wife are depicted as seated statues. Her daughter is between them. The inke back wall (4–5) is less well preserved and contains representations in two groups with three or four registers. In the upper register of the left group, the grave lord is awarded the gold of honor. At the right end is Ramses III. depicted with the blue crown under a canopy. The text refers to his 27th year in office. In the two registers below the sacrificial grave lord is shown in front of sacrificial structures and various relatives. The group on the right shows the grave lord again, as he, among others. by Prince Ramses, later Ramses IV, in the presence of his father Ramses III. is awarded. In the lowest fourth register, a priest probably makes sacrifices to the graveyard and his wife.

Of the right entrance wall (6) only people sitting in the corner are preserved. At the right narrow wall (7) is the seated statue of the tomb lord. On the right rear wall (8) a text of veneration for Osiris is on the left and a man with an inscription on the sacrifice is on the right. There are people sitting underneath. The Door to the main hall shows remnants of text on the post, the grave lord on the lintel and a hymn to Amun-Re on the left reveal.

The left wall of the Longitudinal hall (10) shows the remains of the funeral procession in the presence of the gods Re-Harachte, Isis and Nephthys. Among the participants in the procession are gift-bearers and plaintiffs. The front part of the right wall (11) shows the seated grave gentleman in the upper register. Only a few remains of the lower register have survived. The back part (12) consists of a longer text with the negative confession of sin, i.e. i.e., the grave lord is free from sin.

The Lintel to the chapel (13) shows as a double scene the now lost grave lord who worships Osiris and Isis on the left and Osiris and Nephthys on the right. The left wall (14) of the chapel repeatedly shows the adoring tomb lord in front of Isis in the upper register and in front of Horus in the lower register. The opposite wall (15) is divided by a snake. To the right of her is the grave lord, to the left of the serpent Osiris in front of two rows with deities, in front of him Thoth and Horus. In the back wall niche (16) are the statues of Osiris Wennefer in the middle and to his left and right the grave lord Amenemōpet, who is justified by his parents. On the side walls, the grave lord worships the falcon-headed god Re-Harachte on the left and the ram-headed god Amun-Re-Harachte on the right.

Tomb of the Raya, TT 159

In 2019, two more graves were made accessible, which were restored by the Egyptian Ministry of Antiquities between 2015 and 2018.

The tomb of the Raya, 4 TT 159(25 ° 44 ′ 10 ″ N.32 ° 37 '9 "E), the fourth prophet of Amun, and his wife Mutemwia comes from the 19th dynasty.

Tomb of Niay, TT 286

Immediately next to the previous grave is that of Niay, the scribe of the sacrificial table from the 20th dynasty.

Deir el-Bachīt

On the ridge you can find the extensive remains of the former early Christian Paulos monastery, which is now fenced off. The monastery and its location have been known since the middle of the 19th century. At that time there were still monk cells with painted door arches. A cemetery with around one hundred burials and numerous ostracas (labeled pottery shards) with Coptic documents was also found here. Later excavations have seriously affected the monastery, so that today only a few remains are found. The monastery is the largest in West Thebes and is also the best preserved.

The area has been researched since 2004 by the Institute for Egyptology at the University of Munich and the German Archaeological Institute. The name of the monastery could be derived from the recovered 175 ostraka in 2010, the Paulos Monastery, determine.[9]

The monastery probably existed between the 5th and 10th centuries. It is believed that it might have had its heyday in the 6th to 8th centuries.

So far, the central building of the monastery with the refectory (dining room), farm buildings, monk cells and graves have been exposed. The refectory consists of pairs of seating rings around a brick table. The farm buildings were used to store supplies in masonry containers. Other rooms were used as weaving mills, and the associated loom pits were found here. The monk's cells, including the furniture such as beds and wall niches, were also made of adobe bricks. The location of the monastery church (s) is not yet known. In the cemetery belonging to the monastery, the graves were laid out in rows.

Previous finds include ceramic vessels and a glass bottle that date from the 8th century.

kitchen

There is a small restaurant in the area of Sheikh ʿAbd el-Qurna, more in Gazīrat el-Baʿīrāt and Gazīrat er-Ramla as in Luxor.

accommodation

The closest hotels can be found in the area of Sheikh ʿAbd el-Qurna. There is also accommodation in Gazīrat el-Baʿīrāt and Gazīrat er-Ramla, Ṭōd el-Baʿīrāt, Luxor as Karnak.

trips

The visit of Drāʿ Abū en-Nagā can be combined with a visit to other official graves, e.g. in Sheikh ʿAbd el-Qurna connect. Furthermore, in the south is the temple of Deir el-Baḥrī.

literature

- Shuroy's tomb

- : The Theban Necropolis; Part 1: Private tombs. In:Topographical bibliography of ancient Egyptian hieroglyphic texts, statues, reliefs, and paintings; Vol.1. Oxford: Griffith Inst., Ashmolean Museum, 1970, ISBN 978-0-900416-15-6 , ISBN 978-0-900416-81-1 , P. 20 (plan), 25 f; PDF.

- Roy's grave

- : Le tombeau de Roÿ: (tombeau No 255). LeCaire: Institut Français d'Archéologie Orientale, 1928, Mémoires publiés par les membres de l’Institut français d’archéologie orientale du Caire; 57.1.

- : Documents of the 18th dynasty: translations for issues 17–22. Berlin: academy, 1961, P. 430 (# 851, 2174).

- Amenemōpet's tomb

- : The tomb of Amenemope (TT 148); Vol. 1: Architecture, texts and decoration. Oxford: Aris and Phillips, 2009, Reports / The Australian Center for Egyptology; 27, ISBN 978-0-85668-824-9 . The second volume deals with the archeology of the tomb and the finds, including ceramics.

- Deir el-Bachīt Monastery

- : Deir el-Bachît. In:Helck, Wolfgang; Otto, Eberhard (Ed.): Lexicon of Egyptology; Vol. 1: A - harvest. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 1975, ISBN 978-3-447-01670-4 , Col. 1006.

- : Dēr al-Baḫīt. In:Christian Coptic Egypt in Arab times; Vol. 2: D - F. Wiesbaden: Reichert, 1984, Supplements to the Tübingen Atlas of the Middle East: Series B, Geisteswissenschaften; 41.2, ISBN 978-3-88226-209-4 , Pp. 682-684.

- : The Deir el-Bachit Monastery in West Thebes: Results and Perspectives. In:Kessler, Dieter (Ed.): Texts, thebes, sound fragments: Festschrift for Günter Burkard. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 2009, Egypt and Old Testament; 76, Pp. 92-106.

Web links

- Dra ‘Abu el-Naga / Thebes-West, Website of the German Archaeological Institute

- The double grave complex K93.11 / K93.12 in Dra ‘Abu el-Naga

- Paulos Monastery (Deir el-Bachît)

- Dra ‘Abu el-Naga / Thebes-West (Archived version of March 23, 2014 in the Internet Archive archive.org)

- The late antique Coptic monastery complex Deir el-Bachit in Thebes-West / Dra ’Abu el-Naga, Institute for Egyptology at the University of Munich

Individual evidence

- ↑The results were published in the magazine "Announcements from the German Institute for Egyptian Antiquity in Cairo“Published, for example in volumes 48 (1992), pp. 109–130; 49: 227-238 (1993); 51 (1995), pp. 207-225; 55 (1999), pp. 343-410; 59 (2003), pp. 41-65, 317-388. See also "Egyptian Archeology" (Bulletin), Vol. 7 (1995), pp. 6-8; 10 (1997), pp. 34 f., 14 (1997), pp. 3-6; 22 (2003), pp. 12-15.

- ↑Immediately to the south is a similar facility, K93.12, which was probably owned by the king's mother, Ahmes-Nefertari, belongs.

- ↑: The pyramid complex of King Nub-Cheper-Re Intef in Dra 'Abu el-Naga: a preliminary report. Mainz: from Zabern, 2003, Special publication / German Archaeological Institute, Cairo Department; 24, ISBN 978-3-8053-3259-0 .

- ↑Secret hiding place in the altar, Communication from the German Archaeological Institute of March 25, 2014, accessed on February 1, 2016.

- ↑Champollion, Jean-François: Monuments de l’Égypte et de la Nubie: notices descriptives conformes aux manuscrits autographes rédigés sur les lieux par Champollion le Jeune, Paris: Didot, 1844, Volume 1, pp. 554 f.

- ↑Statue 17.190.1960. Please refer: : The Scepter of Egypt; Vol. II. new York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1990, P. 160 f., Fig. 88.

- ↑: Travels along the Mediterranean, and parts adjacent; in company with the earl of Belmore, during the years 1816-17-18; Vol.1. London et al.: Cadell et al., 1822, P. 261.

- ↑: The Theban necropolis: on the change in the idea of tombs from the XVIII. until XX. dynasty. Mainz: from Zabern, 1996, Thebes; 13, Pp. 434–437, Figs. 329–331.

- ↑Kehrer, Nicole: Letters from the Coptic past ..., Message from the Science Information Service (idw) from October 16, 2011.