View of the village of el-Hammāmīya to the west | ||

| el-Hammāmīya · الهمامية | ||

| Governorate | Asyūṭ | |

|---|---|---|

| Residents | 8.952 (2006) | |

| height | 65 m | |

| no tourist info on Wikidata: | ||

| location | ||

| ||

El-Hammamiya, also el-Hemamieh, el-Hemamija, Arabic:الهمامية, al-Hammāmīya, is a village in central egyptianGovernorateAsyūṭ. About 100 meters north of the village is an ancient Egyptian necropolis (cemetery) from the early and middle 5th dynasty, which belonged to the tenth Upper Egyptian district.

background

location

The village 1 el-Hammāmīya is located on the eastern bank of the Nile in the fruitland about halfway between Asyūṭ and Sōhāg, opposite the city of Ṭimā on the western bank of the Nile, about 10 kilometers southeast of el-Badārī, 42 kilometers southeast of Asyūṭ and 47 kilometers north-northwest of Sōhāg. Both trunk road 02 and the Chizindārīya Canal run along the western edge of the village,الترعة الخزندارية. The village was called earlier too Sheikh Gabir, شيخ جابر, And Nazlat Hammam, نزلة همام,[1] where the current name is probably derived from the latter. In 2006, 8,952 people lived in the village. The main line of business is agriculture. The desert, in which the local cemetery was laid out, already extends to the north and east of the village.

In the northeast of the village is the necropolis of the Gau princes and high officials of the 10th Upper Egyptian Gaus, the Schlangengau Wadjitwhose graves were dug in the slope of the limestone cliff. The quality of the local limestone is rather poor. Nonetheless, the mountains were also used as a quarry.

The village is located about 2.5 kilometers southeast of Hammāmīya ʿIzbat Yūsufto the east of which is the archaeological site of Qāu el-Kabīr or Antaeopolis.

history

The Beginnings of el-Hammāmīya reach into the Badari time (approx. 4500 to 4000 BC), which is occupied by settlement remains about two miles north of the present-day village. The center of the cultural area was el-Badārī, only ten kilometers to the north. Individual finds also belong to the Naqada culture (approx. 4500 to 3000 BC),[2] which the influence of the significantly southern at Naqada in the north of Luxor located culture area. The researched objects include mud huts, graves and animal graves as well as finds such as flint stones, partially decorated ceramics, pearls and tools such as needles.[3] An inscribed cylinder made of ivory comes from the Naqada III period (Protodynastic Period or 0th Dynasty, 3200-3000 BC).[4]

The local cemetery of Old empire was only used during the 5th Ancient Egyptian Dynasty in the Old Kingdom. A cemetery for the following 6th dynasty is unknown. The princes of the tenth Upper Egyptian Gaus of the 12th and 13th Dynasties in the Middle Kingdom settled in Qāu el-Kabīr bury.

In the above-mentioned settlement areas and cemeteries north of today's village a grave was found Pan-burial culture at the time of the Second Intermediate Period, graves from the late and Roman times, finds from the Coptic period as well as ceramics and glassware from the Arab period were uncovered.[5] About the finds from the Coptic settlement, whose former name has not been passed down,[6] include a limestone capital of a church or chapel, the walls of which were once decorated with frescoes, graves, a bronze votive vessel and a papyrus with the Gospel of John from the 4th century.[5][7]

The city was located southeast of the village of el-Hammāmīya at ʿIzbat Yūsuf Antaeopolis / Antaiopolisused in Greek / Ptolemaic and Roman times. Their most important building, the under Ptolemy IV Philopator erected temple, was destroyed in the first half of the 19th century. The residents were buried in the Qāu el-Kabīr cemetery. Unfortunately, it is not known whether and what relationship existed between Antaeopolis and the local late to Coptic settlements.

At least the graves of the Old Kingdom have been around since the first half of the 19th century known. British Egyptologist John Gardner Wilkinson (1797-1875), who stayed in Egypt 1821-1833, 1841-1842, 1848-1849 and 1855, left notes on the tombs of the Old Kingdom in his unpublished manuscripts.[8] In Wilkinson's guidebook Modern Egypt and Thebes from 1843, however, el-Hammāmīya was not included. In the Baedek Upper Egypt Guide of 1891, el-Hammāmīya was mentioned - probably for the first time -, albeit incorrectly.[9]

The excavations carried out in el-Hammāmīya in the predynastic cemeteries of the Missione Archeologica Italiana under the direction of the Italian Egyptologist from 1905–1906 Ernesto Schiaparelli (1856–1928)[7][10] and the 1913–1914 of the Sieglin expedition under the German Egyptologist Georg Steindorff (1861–1951) made photographs and copies of the graves of the Old Kingdom[11] have never been fully published. Some of the finds from the Italian Mission are in the Egyptian Museum in Turin issued.

Reports on the archaeological sites at el-Hammāmīya did not appear until the 1920s and 1930s. The first scientific description of the graves of the Old Kingdom was provided by the German Egyptologist in 1921 Hermann Kees (1886–1964) before,[12] who stayed in Egypt for this 1912–1913. As part of the British Egyptologist Guy Brunton (1878-1948) led expedition of the British School of Archeology in Egypt in 1924 led the British archaeologist Gertrude Caton-Thompson (1888–1985) carried out excavations in cemeteries north of el-Hammāmīya, in which finds from the predynastic period to the Arab period were obtained,[3] and the British Egyptologist William Matthew Flinders Petrie (1853–1942) carried out investigations on the graves of the Old Kingdom.[13] The treatise by Mackay and Petrie was for a long time the best publication on the Old Kingdom tombs of el-Hammāmīya, but it was unfortunately incomplete. It only describes the two graves of Kaichent (A2, A3), the foremost grave of Djefai-ded (A1) is missing.

In 1927 the German Egyptologist published Walter Wreszinski (1880–1935) first results of his photographic expedition[14] and in 1936 the German Egyptologist Hellmut Brunner (1913–1997) a dissertation,[15] in which he presented the state of scientific research on el-Hammāmīya.

Renewed examinations were carried out at the end of the 1980s by the Australian Center for Egyptology under the direction of Ali el-Khouli, which were completed in January 1990. The graves of a third group of graves were also examined and published (see literature).

getting there

In the street

Of Asyūṭ via el-Badārī or from Sōhāg Coming you use the trunk road 02 on the Nilostseite to get to el-Hammāmīya. Over a 1 Canal bridge(26 ° 55 '44 "N.31 ° 29 ′ 14 ″ E) you get to the village. On a dirt road you drive north towards the cemetery, past its west side to its end, until you then get to the 2 Administration building for the inspector and the cash register(26 ° 56 ′ 12 ″ N.31 ° 29 ′ 7 ″ E) got. The vehicle can be parked at the administration building.

Walk along the east side of the cemetery until you reach the stairs to the tombs of the necropolis of el-Hammāmīya.

mobility

The village is not very big and the necropolis is only about 100 meters from the northern edge of the village, so that the distances can also be covered on foot. The streets in the village and on and in the cemetery are just beaten tracks. To get to the tombs from ancient Egyptian times, you have to climb a long staircase. It's a little easier to walk next to these stairs.

Tourist Attractions

Pharaonic monuments

The archaeological site is open from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. The entrance fee is LE 40 for foreigners and LE 20 for foreign students, the camera ticket LE 300 (as of 11/2019). The use of smartphones is free.

Stairs to the graves of the A group

Graves of the B group

Limestone quarry

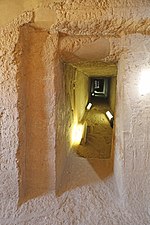

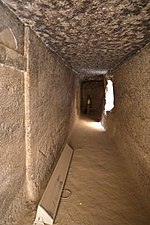

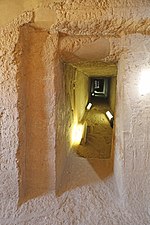

There are three groups of rock graves belonging to the necropolis. In the northernmost A group, which was laid out in the early 5th dynasty, the three most important tombs are accessible to visitors, which are also terraced and close together. These graves can be reached via a common pathway, which now has a staircase. The middle tomb of Kai-chent is the most beautiful and best preserved.

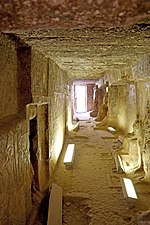

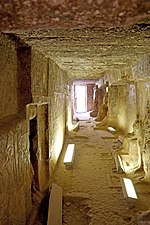

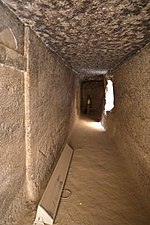

These three graves are similar, so the description of the architectural structure should be placed first. The aim of the builders was to make their graves look like Mastaba graves possessed. The superstructures, however, were not bricked, but carved out of the rock. For this purpose, corridors were created on the south, east and west sides. Access was via the south corridor, which already contained the first reliefs and statue niches. This is followed by a narrow corridor to the north, which functioned as a cult chamber. This irregularly shaped corridor was covered and had most of the decorations, which were executed as bas-relief. The themes of the relief scenes come from everyday life and from the cult of the dead. The northern corridor was made much simpler and not decorated, as it had no other purpose other than the boundary of the rock mastaba. In the case of the foremost (western) grave, the north corridor is completely absent. The Felsmastabas the Fraser graves at Ṭihnā el-Gebel are related in form.

As with masonry mastabas, the grave shafts are located in the mastabak body and cannot be reached from the cult chamber.

From east to west you can reach the following graves in their chronological order:

- 1 Grave of Kaichent and his wife Chentikaues (A3). In front of the entrance to the grave there is an unsecured trench that leads to another grave, the grave of Idi.

Kaichent's tomb

South corridor

Kaichent and his wife

Cult chamber

Sons of the Kaichent

- 2 Grave of Kaichent and his wife Jufi (A2). This grave is the most beautiful or best preserved grave in the necropolis. The grave lord Kaichent (KꜢ (.j) -ḫnt) owned a. the title biological king's son, acquaintance of the king, head of the phyls of Upper Egypt and was the son of Kaichent, the owner of the grave A3. The titles of his wife Jufi (Jwfj) were among others. Prophetess of Hathor, mistress of the sycamore, and prophetess of Neith north of the wall. The grave also has a drainage channel that leads from the south corridor to the outside.

Kaichent's tomb, looking southeast

Statue of the Kaichent

Cult chamber

Statues of the Kaichent family

False door

Dining table scene on the false door

Men lead a cow

Kaichent family

Kaichent and his wife

Victim-bearer

Wife Jufi on a papyrus paper

Geese over a papyrus nap

- The 3 Tomb of the Djefaided (A1), incorrectly called the tomb of Nemu, is the foremost and lowest tomb of the A group. The grave can be reached via a narrow forecourt with an undecorated grave on each side. To the north of the forecourt there are five grave shafts in the rock. Behind the entrance you get to the 3 meter long and 1.25 meter wide south corridor, from which the 7 meter long, 1.7 meter wide and 1.8 to 2 meter high cult chamber branches off to the north. The grave has no north corridor. The bas-reliefs, mainly in the south corridor, are almost without inscriptions. However, on the left reveal of the entrance above the remains of the tomb Djefaided (ḎfꜢ (.j) -dd) and his wife Hekenuhedjet (Ḥknw-ḥḏt) a four-column inscription identifying the grave lord and his wife:

- “(1) Head of the ka- Servant, possessor of worship, (2) ... his master, (3) loved daily by his master, Djefaided; (4) the priestess of Hathor, mistress of Dendera, Hekenuhedjet. "[16]

- The right reveal was probably a mirror image. Here you can see the grave lord with staff and scepter with his wife much better. However, there is no inscription.

Tomb of the Djefaided

Family of the Djefaided

Statue of the Djefaided

Djefaided

Wife and children

Cult chamber

- The south wall of the south corridor shows the grave lord, his wife and probably the oldest son in life size. There are three more children in front of the tomb and a smaller child behind him. According to the author el-Khouli, the scanty remnants of his name Nianch-Userkaf are to be found in front of the eldest son. At the back of the corridor is the statue of the tomb lord in a niche. On the north side of the corridor, the grave lord, his wife and their children are depicted again. The cult chamber has, apart from two unlabeled false doors with a sacrificial plaque on the west side, no further decoration.

To the southeast of the graves of the A group are the rock graves of the B group. These are simple rock chambers in which there are also the grave shafts and a niche in the rear wall as well as a sacrificial tablet in front of the niche. These graves have no decoration, apart from the door drum above the door.

The graves of the are on the neighboring hill to the south C group. They were created around the middle of the 5th dynasty, i.e. later than the graves of the A group, and their shape is based on the graves of the A group. However, the corridor system has been simplified significantly. Only one grave - that of Re-hetep / Rahotep (Rʿ-ḥtp, Grave C5) - has a decoration of which only a few remains of scenes have survived. The representations were applied in color on white plaster. The latter grave cannot be visited.

Village

- 4 Islamic cemetery in the north of the village.

- There are small mosques in the village, including the 5 Mosque of the Ḥāgg Abū Dahab, مسجد الحاج أبو دهب.

kitchen

Restaurants can be found in Asyūṭ and Sōhāg.

accommodation

There are hotels in Asyūṭ and Sōhāg.

Practical advice

trips

The following destinations can be visited south of el-Hammāmīya and also on the east side of the Nile:

- 6 ʿIzbat Yūsuf, عزبة يوسف- Monumental royal tombs of the 12th and 13th dynasties of Qāu el-Kabīr. About 2.5 kilometers southeast of el-Hammāmīya.

- 7 Deir el-Anbā Harmīnā es-Sāʾih, دير الأنبا هرمينا السائح- Monastery of el-Anba Harmina. About 3 kilometers southeast of el-Hammāmīya.

literature

- : The Old Kingdom tombs of El-Hammamiya. Sydney: Australian Center for Egyptology, 1990, Reports / The Australian Center for Egyptology, Sydney; 2, ISBN 978-0-85837-702-8 .

- : The Governors of the WꜢḏt-Nome in the Old Kingdom. In:Göttinger Miscellen: Contributions to the Egyptological discussion (GM), ISSN0344-385X, Vol.121 (1991), Pp. 57-67.

Individual evidence

- ↑: al-Qāmūs al-ǧuġrāfī li-’l-bilād al-miṣrīya min ʿahd qudamāʾ al-miṣrīyīn ilā sanat 1945; Vol. 2, Book 4: Mudīrīyāt Asyūṭ wa-Ǧirḥā wa-Qinā wa-Aswān wa-maṣlaḥat al-ḥudūd. Cairo: Maṭbaʿat Dār al-Kutub al-Miṣrīya, 1963, P. 40 (numbers above).

- ↑: el-Hemamija. In:Helck, Wolfgang; Westendorf, Wolfhart (Ed.): Lexicon of Egyptology; Vol. 2: Harvest Festival - Hordjedef. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 1977, ISBN 978-3-447-01876-0 , Col. 1116.

- ↑ 3,03,1: The Badarian civilization and predynastic remains near Badari. London: British School of Archeology in Egypt, 1928, British School of Archeology in Egypt; 46, Pp. 69-116, panels lxii-lxxxv; PDF.

- ↑: Qau and Badari; 1. London: Quaritch, 1927, British School of Archeology in Egypt; 44, P. 18, plate xx.68; PDF.

- ↑ 5,05,1: Qau and Badari; 3. London: Quaritch, 1930, British School of Archeology in Egypt; 50; PDF.

- ↑: al-Hammāmīya. In:Christian Coptic Egypt in Arab times; Vol. 3: G - L. Wiesbaden: Reichert, 1985, Supplements to the Tübingen Atlas of the Middle East: Series B, Geisteswissenschaften; 41.3, ISBN 978-3-88226-210-0 , P. 1078 f.

- ↑ 7,07,1: Scavi nella necropoli di El Hammamiye. In:Aegyptus: rivista italiana di egittologia e di papirologia, ISSN0001-9046, Vol.20 (1940), Pp. 277-293.

- ↑: Upper egypt: sites. In:Topographical bibliography of ancient Egyptian hieroglyphic texts, statues, reliefs, and paintings; Vol.5. Oxford: Griffith Inst., Ashmolean Museum, 1937, ISBN 978-0-900416-83-5 , Pp. 7-9; PDF. Some of the manuscripts are now in the Bodleian Library in Oxford.

- ↑: Egypt: Handbook for Travelers; Part 2: Upper Egypt and Nubia to the Second Cataract. Leipzig: Baedeker, 1891, P. 52.

- ↑: The Collezione predinastica del Museo Egizio di Torino: uno studio integrato di archivi e reperti. Trento: University of Trento, 2016.

- ↑Notes and News. In:Journal of Egyptian Archeology (JEA), ISSN0075-4234, Vol.1,3 (1914), Pp. 212-223, especially p. 217. — : The bas-reliefs of the Old Kingdom: 2980-2475 BC Chr .; Material on Egyptian cultural history. Heidelberg: winter, 1915, Treatises of the Heidelberg Academy of Sciences, Philosophical-Historical Class; 3, P. Iv.

- ↑: Studies in Egyptian provincial art. Leipzig: Hinrichs, 1921, Pp. 17-32, panels iii-vi.

- ↑: Bahrain and Hemamieh. London: Quaritch, 1929, British School of Archeology in Egypt; 47, P. 31 ff.

- ↑: Report on the photographic expedition from Cairo to Wadi Halfa for the purpose of completing the collection of materials for my atlas on ancient Egyptian cultural history. Hall a. S.: Niemeyer, 1927, Writings of the Königsberg learned society, humanities class; 4.2, Pp. 60-63, plate 22.B.

- ↑: The facilities of the Egyptian rock tombs up to the Middle Kingdom. Glückstadt-Hamburg; new York: Augustine, 1936, Egyptological research; 3, Pp. 20-22, 78 f; PDF.

- ↑Khouli, 1990, p. 24 f.